Book One

Chapter One — The Calm Before the Drums

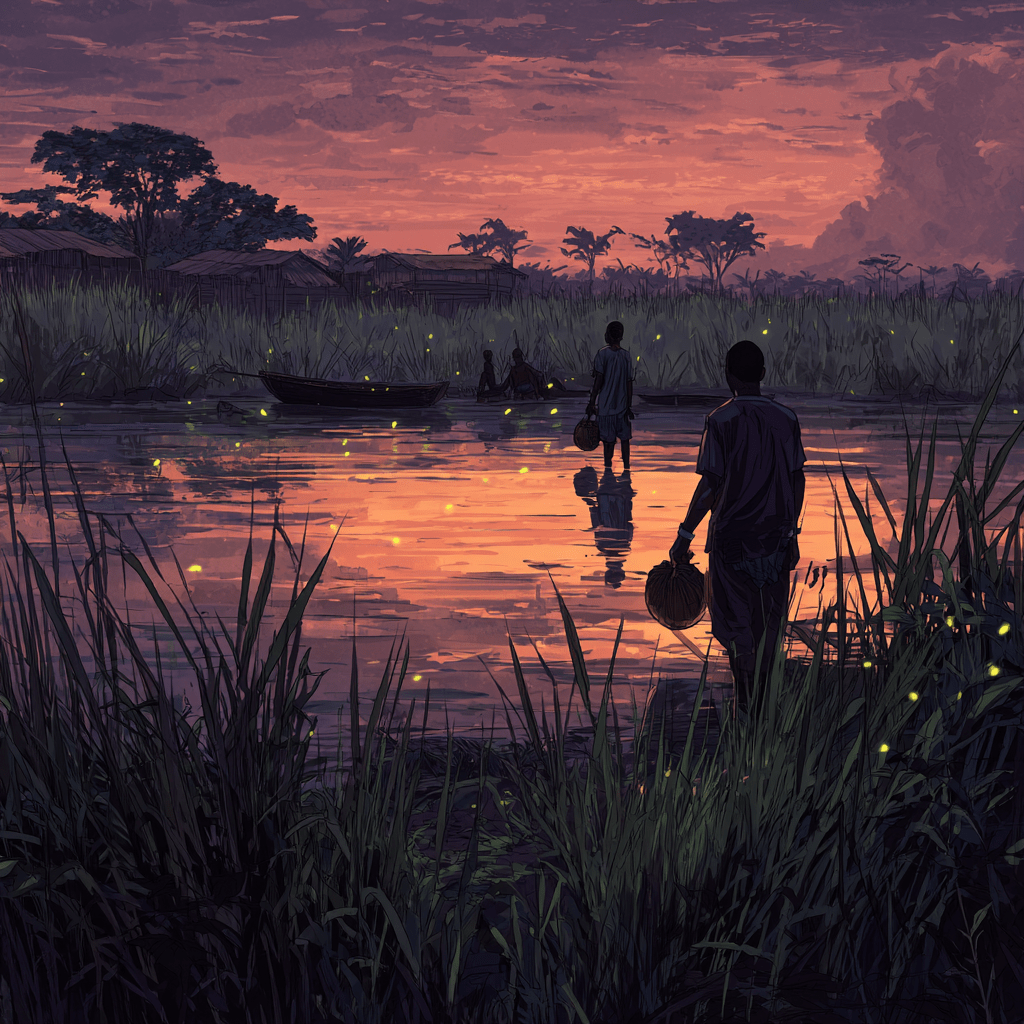

The morning sun rose gently over Nsugbe, spilling gold over the red earth and the glistening thread of the Omambala River. Mist still clung to the tall grasses, and the air smelled of palm wine, yam smoke, and dew. The village stirred slowly, native cocks crowing, pestles thudding in mortar, laughter floating between huts roofed with dry palm fronds.

It was peace — the kind of peace that sings so softly, people forget it can ever end.

By the riverbank, Nnenna knelt, rinsing a basket of bitterleaf in the flowing water. Her skin gleamed like wet bronze, and streaks of nzu — sacred white chalk — marked her forehead and arms in delicate swirls. Her mother, Obianuju, always said the chalk reminded the spirits that a daughter of the earth was pure in heart. But Nnenna liked it because it made her look fierce — like the masked dancers during the New Yam festival.

Behind her, children splashed in the shallow water, laughing as they chased tiny fish.

Further upriver, fishermen pushed their canoes from the shore, calling out greetings.

From the village square came the rhythmic sound of ogene — iron gongs — summoning women to the market.

“Nnenna!” her mother’s voice floated from the hill above.

She turned to see Obianuju waving a calabash. “Your father wants palm wine before the sun grows proud!”

Nnenna sighed, smiling. “Tell Papa I will bring it when the river finishes telling me her secrets.”

Her mother laughed, shaking her head. “Ah, this girl! One day the river will carry you away.”

“Then it will return me,” Nnenna said, standing, her wet wrapper clinging to her legs. “I am Omambala’s daughter.”

She began the climb back toward the village. From that height, Nsugbe stretched below her — round huts scattered like cowries, smoke rising in lazy threads, goats bleating, and the people of the land moving in harmony. The udara tree at the heart of the square towered over all, its branches filled with the chatter of birds and the laughter of children.

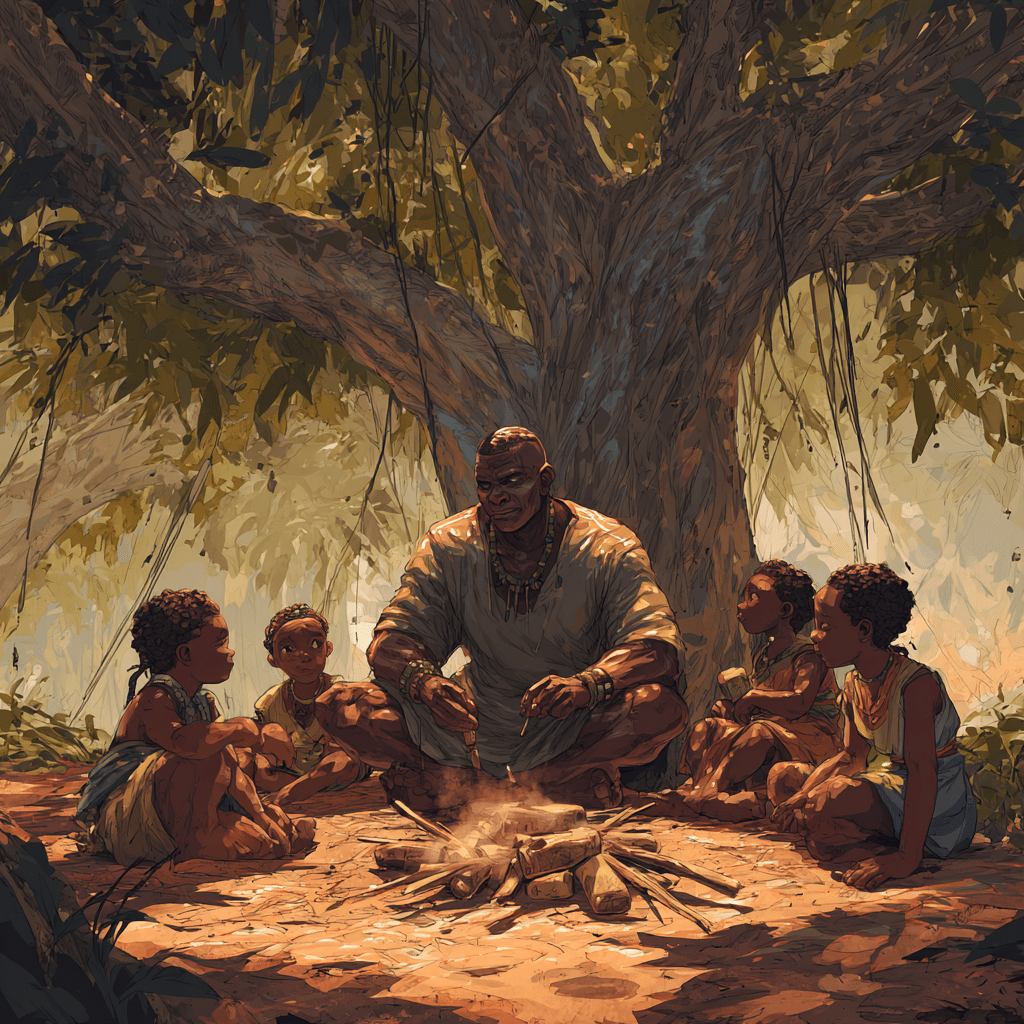

Under that same tree sat a man the villagers called Onye Nkuzi — the Teacher.

He was a quiet one, his age hard to tell. His beard was short, peppered with gray, and a thin scar crossed his left cheek like a forgotten story. Children gathered before him, scratching Igbo letters into the sand with sticks as he spoke in his calm, even tone.

> “Every word you speak carries the breath of your ancestors,” he said, drawing a symbol on the ground.

“To forget the word is to forget the spirit.”

The children murmured in awe, tracing the marks after him. Nnenna often paused by the tree just to listen. There was something about his voice — like river water running over stones, soft but full of secrets. He was not from Nsugbe; that much everyone knew. Some said he came from Awka, others whispered he had wandered from the north after surviving a war. No one knew for sure, and Onye Nkuzi never said.

As Nnenna passed, he looked up briefly and smiled — that same knowing smile that made her feel seen.

“Ah, Nnenna. The river greeted you this morning?”

She stopped. “She did. She told me you stare too long at the north.”

The children giggled, and the teacher’s smile faded just slightly — like a shadow crossing the sun.

“Perhaps,” he said softly. “But even the river must look beyond her banks sometimes.”

Nnenna tilted her head, not sure what he meant, but before she could ask, the gong sounded again — the call for the women’s market.

.

.

.

By midday, Eke Market was alive. Stalls lined with woven mats, heaps of pepper, kola nuts, palm oil glistening in clay pots. The air buzzed with bargaining voices and laughter. Nnenna followed her mother, carrying baskets on her head. Eze Ukwu, her father, sat under a small canopy at the market’s edge — the staff of ofo resting across his knees. As chief elder of Nsugbe, he oversaw trade disputes and blessed every new venture with prayers to Ani, the Earth Mother.

He looked up as his daughter approached.

“Ah, the river’s child returns,” he said with a small smile. “Did Omambala teach you how to fetch wine yet?”

“Papa,” Nnenna laughed, setting the basket down, “if you stop teasing me, maybe I will pour you some.”

The old man’s laughter rumbled deep like thunder. But when the traders from Anam arrived later that day, his mood changed. Their leader bowed low, face lined with fatigue.

“Eze Ukwu,” he said, “we bring pepper and salt — but also news. From the north. Strange riders — men with white horses and long swords. They burn and take, saying they fight for Allah.”

The crowd murmured uneasily.

Eze Ukwu’s eyes narrowed. “Far north or near?”

“Too near,” came the answer. “They passed through Lokoja. Villages fall like dry leaves.”

Silence fell over the market. Somewhere in the distance, a goat bleated. Nnenna’s hand tightened around her basket handle. She didn’t yet understand what war meant — but she saw the look on her father’s face. It was the same look he had when storms gathered over the Omambala.

That evening, when the sun sank behind the palms, Onye Nkuzi stood alone by the riverbank. He held a small carved charm in his hand and whispered words no one nearby could understand. The wind stirred. The waters rippled faintly, as though listening.

Nnenna saw him from afar. She wanted to ask what he knew — why his eyes seemed to carry more than a teacher’s burdens. But something in the air that night felt heavy, almost sacred.

And far beyond the hills of Nsugbe, thunder rumbled — not from the sky, but from hooves.

The calm had begun to break.